In Part 1, we used the jobbR package to collect information for data scientist and data analyst positions from the Indeed API. We found that data scientists earned significantly more than data analysts (no big surprises there). Given the disparity in salary, can we identify the difference in skills required by each group. If so, maybe we can predict data scientist roles from the job descriptions?

Data Collection

This section will be quite similar to Part 1. We’ll extract all data scientist and data analyst jobs in London from the Indeed API and then filter out all junior/senior positions. As it’s essentially a repeat of Part 1, we don’t need to spend much time on this step.

## if you haven't already installed jobbR

# devtools::install_github("dashee87/jobbR")

## loading the packages we'll need

require(jobbR)

require(dplyr)

require(rvest)

require(stringr)

require(plotly)

# collecting data scientist jobs from the Indeed API

dataScientists <- jobSearch(publisher = "publisherkey", query = "data+scientist",

country = "uk", location = "london", all = TRUE)

# collecting data analyst jobs from the Indeed API

dataAnalysts <- jobSearch(publisher = "publisherkey", query = "data+analyst",

country = "uk", location = "london", all = TRUE)

# removing junior and senior roles

dataScientists <- dataScientists[grepl(

"data scientist", dataScientists$results.jobtitle,ignore.case = TRUE) &

!grepl("senior|junior|lead|manage|intern|analyst|graduate|chief",

dataScientists$results.jobtitle,ignore.case = TRUE),]

dataAnalysts <- dataAnalysts[grepl(

"data analyst", dataAnalysts$results.jobtitle,ignore.case = TRUE) &

!grepl("senior|junior|lead|manage|intern|scientist|graduate|chief",

dataAnalysts$results.jobtitle,ignore.case = TRUE),]

dataScientists <- dataScientists[! duplicated(dataScientists$results.jobkey),]

dataAnalysts <- dataAnalysts[! duplicated(dataAnalysts$results.jobkey),]

Like salaries, the Indeed API doesn’t return full job descriptions (though it does return the first few lines- see the results.snippet column). It does provide a url for the job description, which we can thus scrape.

# scrape job description webpages

ds_job_descripts <- unlist(lapply(dataScientists$results.url,

function(x){read_html(x) %>%

html_nodes("#job_summary") %>%

html_text() %>% tolower()}))

da_job_descripts <- unlist(lapply(dataAnalysts$results.url,

function(x){read_html(x) %>%

html_nodes("#job_summary") %>%

html_text() %>% tolower()}))

We now have two vectors of job descriptions- one for each job type. In both vectors, each element is just a string.

# an example data scientist job description

# I picked 49 as it's one of the shorter ones

ds_job_descripts[49]

## [1] "data scientist, python x2\ncentral london\n\n£doe\n\ndata scientists are required by a leading data insights company, based in the city.\n\nthese data scientist opportunities requires those who are able to perform early stage research and development for our clients internal data, in order to help perform discovery and proof of concept in house.\n\nalong with these data scientist positions you<U+0092>ll be expected to design and build software products in python and sql. those who are able to provide a generous like for like comparison will prove highly successful in their application. any agile experience will also be a huge advantage.\n\nto apply for these data scientist roles please send your cv to imogen morpeth at arc it recruitment or call for a consultation\n\ndata scientist, python, sql, proof of concept, data driven research, data stories, numpy, scikit-learn, matplotlib, pandas, statsmodels, seaborn"

To gain any insights from this somewhat messy data, we need to isolate the relevant information. We’re going to employ a bag-of-words model. Put simply, we’ll reduce the strings to specific words of interest and count the number of occurences of each word in each string. We just need to decide which words we’re interested in. I’ve constructed a data frame called skills, which represents the skills that I’d expect to find in data scientist/analyst job postings.

skills=data.frame(

title=c("R", "Python", "SQL", "Excel", "Powerpoint", "KPI", "Dashboard",

"Matlab", "Tableau", "Qlikview", "D3", "SAS", "SPSS", "BI", "C++",

"Java", "Javascript", "Ruby", "Scala", "Php", "VBA",

"Machine Learning", "Big Data", "Modelling", "Communication",

"Stakeholder", "Masters", "PhD", "Hadoop", "Spark", "Map Reduce",

"Pig", "Hive", "NoSQL", "MongoDB", "Cassandra", "Mahout",

"Google Analytics", "Adobe", "API", "NLP", "Maths", "Statistics",

"Physics", "Computer Science", "Engineering", "Economics",

"Finance"),

regex=c("r", "python|numpy|pandas|scikit", "sql|mysql|sql server|mssql",

"excel","powerpoint|power point", "dashboards?", "kpis?",

"matlab", "tableau", "qlikview", "d3", "sas", "spss",

"bi|business intelligence", "c\\+\\+|c/c\\+\\+", "java",

"javascript", "ruby", "scala", "php", "vba?|visual basic",

"machine learning", "big data", "modelling|modeling",

"communication", "stakeholders?", "masters?|msc","phd", "hadoop",

"spark", "map reduce|mapreduce|map/reduce", "pig", "hive", "nosql",

"mongodb", "cassandra", "mahout","google analytics|GA|big query",

"adobe", "apis?", "nlp|natural language", "math?s|mathematics",

"statistics|biostatistics", "physics", "computer science",

"engineering", "economics", "finance"),

stringsAsFactors = FALSE

)

The skills dataframe consists of 48 skills (don’t worry, I’m also not an expert in a few of them). The title column is the name of the skill, while the regex column represents the regex pattern we seek to match in our descriptions. For example, the regex entry for Maths is math?s|mathematics, which means we’re looking for words matching ‘math’, ‘maths’ or ‘mathematics’.

So, we have a bag and we need to put some words in it; we calculate the number of occurences of each word in each string.

# count number of occurences of each word in the skills dataframe in

# the data science job descriptions

ds_occurs <- matrix(unlist(lapply(skills$regex,

function(x){str_count(ds_job_descripts,

paste0("\\b", x, "\\b"))})),

length(ds_job_descripts), length(skills$title))

# count number of occurences of each word in the skills dataframe in

# the data analyst job descriptions

da_occurs <- matrix(unlist(lapply(skills$regex,

function(x){str_count(da_job_descripts,

paste0("\\b", x, "\\b"))})),

length(da_job_descripts), length(skills$title))

head(ds_occurs[,1:10])

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6] [,7] [,8] [,9] [,10]

## [1,] 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

## [2,] 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

## [3,] 2 2 2 1 0 0 0 0 1 1

## [4,] 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0

## [5,] 2 2 1 1 0 1 0 0 2 0

## [6,] 1 5 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

We have two matrices that represent the number of occurences of each word in each data scientist/analyst job description. For example, python appeared 5 times in the sixth data scientist job description. I’m not so interested in the number of occurences but whether the word occured at all. Some job descriptions can be quite repetitive, so the number of occurences could be a little misleading. We’ll convert the two matrices to binary matrices (1: the word occured in the job description; 0: it didn’t).

ds_occurs <- ifelse(ds_occurs>1, 1, ds_occurs)

da_occurs <- ifelse(da_occurs>1, 1, da_occurs)

We can plot the frequency of each skill in the job descriptions, split by job type.

plot_ly(rbind(data.frame(job = "Data Scientist",

skills = skills$title,

prop = round(

100*apply(ds_occurs, 2, sum)/nrow(ds_occurs), 2)),

data.frame(job = "Data Analyst",

skills = skills$title,

prop = round(

100*apply(da_occurs, 2, sum)/nrow(da_occurs), 2))),

x = ~skills, y = ~prop, color= ~job, type = 'bar') %>%

layout(margin = list(b = 109),

xaxis = list(title = "", tickfont = list(size = 12)),

yaxis = list(title =

"<b>Appearance in Job Description (% Job Postings)</b>",

titlefont = list(size = 16)),

title = "<b>Job Description Skills: Data Scientist v Data Analyst</b>",

titlefont = list(size=17)) %>%

layout(legend=list(font = list(size = 16))) %>%

layout(autosize = F, width = 1200, height = 800)

Apologies for small text on the x-axis, click here for a better version.

It’s clear from the graph that the skill set of data scientists and data analysts differ significantly. It’s interesting to note that Python narrowly beats R as the most commonly requested skill for data scientists. Excel is the most popular skill for data analysts, followed closely by SQL. In fact, the ubiquity of SQL is apparent by its relatively high frequency for both job types. So, if you’re looking to learn data science/analytics, SQL might be the place to start.

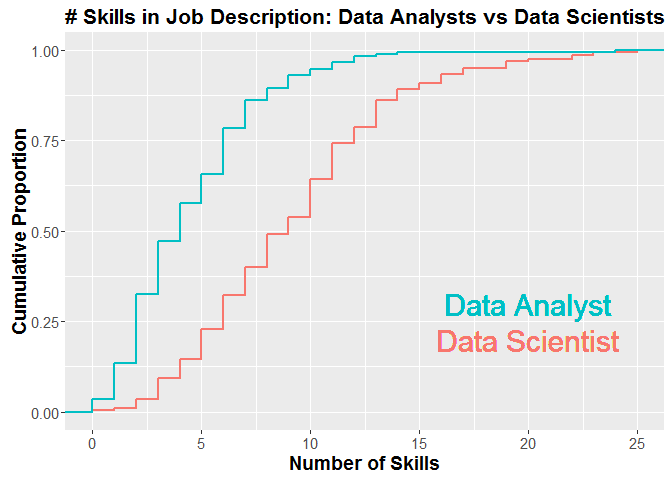

The bars generally appear much lower for the data analyst group, which suggests that these postings tend to have less emphasis on hard skills (or at least less emphasis on the skills inlcuded in the skills data frame). We can plot the cumulative distribution of the number of different skills mentioned per job description. It confirms our hypothesis that data analyst jobs include fewer easily defined skills, as that curve is clearly shifed to the lower values.

ggplot(rbind(data.frame(type = "Data Scientist",

num_skills = apply(ds_occurs,1,sum)),

data.frame(type = "Data Analyst",

num_skills = apply(da_occurs,1,sum))),

aes(num_skills, colour = type)) + stat_ecdf(size = 1) +

geom_text(size=8, aes(20, .3, label = "Data Analyst", color = "Data Analyst")) +

geom_text(size=8, aes(20, .2, label = "Data Scientist", color= "Data Scientist")) +

labs(title = "# Skills in Job Description: Data Analysts vs Data Scientists",

x = "Number of Skills", y = "Cumulative Proportion") +

theme(axis.title = element_text(size = 14,face = "bold"),

plot.title = element_text(size = 16,face = "bold"), legend.position = "none",

axis.text = element_text(size = 11))

Naive Bayes

Okay, we’ve identified a host of features that vary considerably across our two groups. We’ll use a Naive Bayesian Classifier to classify job descriptions as data scientist or data analyst positions. We’ll implement it as a binary classifier, where data scientist equates to TRUE. We’ll run a 70:30 test. The model will be trained on 70 % of the data and we’ll test its performance on the remainder of the dataset. First, we’ll combine the two dataframes and construct the training set.

all_jobs <- rbind(dataScientists, dataAnalysts)

all_job_descripts <- c(ds_job_descripts, da_job_descripts)

all_occurs <- rbind(ds_occurs, da_occurs)

# constructing training set (random sample 70 % of the size of the total set)

set.seed(1000)

training=sample(1:nrow(all_jobs),floor(7*nrow(all_jobs)/10))

Naive Bayes is a relatively simple (yet powerful) machine learning technique, which has been employed extensively in document classification (e.g. spam filters). It’s founded on Bayes Theorem, with the assumption that each feature is independent. That assumption is simplistic (that’s why it’s called naive) and unlikely to hold in reality. For example, a job description containing ‘Excel’ is more likely to contain ‘VBA’ than one without ‘Excel’. Nevertheless, Naive Bayes is fast, flexible and well suited to the task at hand.

To construct our Naive Bayes model, the priors are simply the proportion of training documents that belong to either class (data scientist or data analyst in our case). We calculate the proportion of occurences of each word for each job type (similar to the bar chart) (e.g. P(Python| Data Scientist) ≅ 0.7 and P(Python| Data Analyst) ≅ 0.1). We also factor in skills that are missing from the description (e.g. P(Python Missing| Data Scientist) = 1 - P(Python| Data Scientist) ≅ 0.3) (this approach is commonly called Bernoulli Bayes).

We score each classification class by multiplying the priors by the likelihood probabilities for each word that occurs and doesn’t occur in the text. As computers can struggle with the accuracy of very small numbers, models tend to take the log probabilities. So, instead of multiplications, we sum the logs. The class with the higher score is deemed the winner.

Naive Bayes can be impleneted via the e1071 and klaR packages. However, as I couldn’t find Bernoulli Bayes within either, we’ll configure and evaluate our model manually.

# we determine the class of each training document by checking the row number

# against the number of rows in the training set

# If the row number is greater than the number of rows in the dataScientists

# dataframe, then it's a data analyst position

#calculating proportion of word occurences e.g. P(Maths| Data Scientist)

ds_probs <- apply(all_occurs[training[training <= nrow(dataScientists)],],

2,function(x)(1+sum(x>0))/(2+length(x)))

da_probs <- apply(all_occurs[training[training > nrow(dataScientists)],],

2,function(x)(1+sum(x>0))/(2+length(x)))

ds_prior <- sum(training <= nrow(dataScientists))/length(training)

all_occurs <- ifelse(all_occurs==0, -1, all_occurs)

training_output=data.frame(

num=training,

job_type=training <= nrow(dataScientists),

naive_ds= apply(t(t(all_occurs[training,])*ds_probs), 1, function(x){

log(ds_prior) + sum(log(ifelse(x<0, 1+x, x)))}),

naive_da= apply(t(t(all_occurs[training,])*da_probs), 1, function(x){

log(1 - ds_prior) + sum(log(ifelse(x<0, 1+x, x)))}))

training_output$naive <- training_output$naive_ds > training_output$naive_da

head(training_output)

## num job_type naive_ds naive_da naive

## 1 120 TRUE -17.52841 -23.164360 TRUE

## 2 277 FALSE -15.40111 -9.761314 FALSE

## 3 42 TRUE -20.19398 -40.916161 TRUE

## 4 251 FALSE -17.40322 -16.980370 FALSE

## 5 187 TRUE -17.90851 -23.350003 TRUE

## 6 25 TRUE -20.34700 -26.445036 TRUE

table(training_output[c("job_type","naive")])

## naive

## job_type FALSE TRUE

## FALSE 116 3

## TRUE 14 122

It looks like our model performed well on the training set (only 17/255 incorrect classifications). Let’s really test its accuracy by evaluating its performance on the remaining 30 % of the dataset.

test_output=data.frame(

num = as.vector(1:nrow(all_jobs))[-training],

job_type = all_jobs[-training,]$query=="data scientist",

naive_ds = apply(t(t(all_occurs[-training,]) * ds_probs),

1, function(x){prod(ifelse(x<=0, 1+x, x))}),

naive_da = apply(t(t(all_occurs[-training,]) * da_probs),

1, function(x){prod(ifelse(x<=0, 1+x, x))}))

test_output$naive <- test_output$naive_ds>test_output$naive_da

table(test_output[c("job_type", "naive")])

## naive

## job_type FALSE TRUE

## FALSE 50 3

## TRUE 6 51

Our relatively simple Naive Bayes model correctly predicted the job type with about 90 % accuracy (a better estimate of the range could be derived from k-fold or monte carlo cross validation). The results are summarised in pie charts (an important skill I forgot to include in my skills dataframe).

plot_ly() %>%

add_pie(data = count(filter(test_output, job_type) %>%

mutate(job_type = "Data Scientist") %>%

mutate(job_type, naive =

ifelse(naive, "True Positive",

"False Negative")), naive),

labels = ~naive, values = ~n, name = "Data Scientist",

domain = list(x = c(0, 0.47), y = c(0.2, 1))) %>%

add_pie(data = count(filter(test_output, !job_type) %>%

mutate(job_type = "Data Analyst") %>%

mutate(job_type, naive =

ifelse(!naive, "True Negative",

"False Positive")), naive),

labels = ~naive, values = ~n, name = "Data Analyst",

domain = list(x = c(0.53, 1), y = c(0.2, 1))) %>%

add_annotations(

x = c(27,21.6,25.4,20),

y = c(-0,-0.7,-0.7,-1),

xref = "x2",

yref = "y2",

text = c("","<b>Data Scientist</b>","<b>Data Analyst</b>",""),

showarrow = FALSE) %>%

layout(title = "Predictive Accuracy of Naive Bayes Data Scientist Model",

xaxis = list(showgrid = F, zeroline = F, showticklabels = F),

yaxis = list(showgrid = F, zeroline = F, showticklabels = F),

margin = list(b = 0))

I’m sure more sophisticated techniques (support vector machines, recursive double corkscrew neural nets (RDCNNs)- one of those may have been made up) could have achieved even better predictions, but I’m actually more intrigued by the errors.

Become a Data Scientist (The Easy Way)

Imagine you’re a recent graduate or just someone looking to get into data science: you could make yourself more employable by acquiring a broad subset of the skills in the skills dataframe… or you could find an easy route through our Naive Bayes model. The model has two types of errors: false positives (FPs- mispredicted data analyst positions) and false negatives (FNs- mispredicted data scientist positions).

Starting with the FPs, as we saw earlier, data analyst jobs tend to have fewer skills mentioned in the job description. That means the FPs advertise numerous skills more typical of a data scientist. Thus, the FPs would appear to be bad choices for jobseekers, as you’d possibly be doing the job of a data scientist with the title (and salary) of a data analyst.

# false positives

FPs <- filter(test_output,!job_type & naive)$num

# example false positive job description

all_job_descripts[FPs[1]]

## [1] "we are nexmo. we are an emerging leader in the $100b+ cloud communication and telecom markets. customers like airbnb, viber, line, whatsapp, snapchat, and many others depend on our communications platform to connect with their customers.\n\nas businesses continue to shift to a real-time, customer-centric communications model, we are experiencing a time of explosive growth\n\nthe data analyst will support the business operations function through the analysis of data and trends about quality, revenue, profits, payments, fraud and client behaviour. this key-role will help the team scale by allowing the managers to turn data into insights and thus have an impact in the business side.\n\nyou will\n\nmanipulate and transform data into insight to support the business\n\ndesign, build, run and improve reports\n\nidentify and develop possible data sources that are not currently covered\n\nprovide the critical analytical thinking on various projects and initiatives\n\nsuggest better ways of accessing and understanding data, thus allowing us to continuously improve\n\ndesired skills and experience\n\neducated to degree level\n\nstrong analytical skills\n\nexperience in a business intelligence or data function\n\nhighly proficient in data-related languages (hadoop, r, pig, sql, python<U+0085>)\n\nhighly proficient in data analysis tools (bi, tableau, matlab...)\n\na naturally curious person wanting to continually learn\n\nexcellent attention to detail and the ability to juggle multiple projects in a fast-paced environment\n\nstructured simplicity\n\nhighly organised\n\nwhy nexmo...our values!\n\nwe value disruptive innovation, getting things done, and working with passion and integrity are the values that matter at nexmo. we are on a mission to enable simplified communications between enterprises and their customers by empowering our employees. we strive for passion and integrity, both personally and professionally.\n\nwe have achieved significant growth by hiring exceptional people. we have big goals, and we want the people who join us to be self confident, focused on customers and delivery, and who are structured and committed in their approach. we value those who will help us continue this spirit. if this appeals to you then we encourage you to apply."

As for the FNs, these are data scientists jobs with few skills mentioned in the job description. Unfortunately, this could happen if the text wasn’t scraped well (sometimes the whitespace between words isn’t preserved), or if I overlooked some skills in the skills data frame (e.g Hbase, perl, pie charts). These caveats aside, we should be able to find a nice vague data analyst-esque role that would serve as the perfect entry point into the gilded world of data science.

# false negatives

FNs <- filter(test_output,job_type & !naive)$num

# example false negative job description

all_job_descripts[FNs[1]]

## [1] "data scientist / story teller\n\ndo you like stories? we have thousands, hidden away in a sea of data and we are looking for the right person to help unlock them.\n\nas a data scientist you will enjoy the challenge of teasing out the most valuable insights from vast collections of dynamic and rapidly growing data. you will be a technical leader that enjoys developing and delivering innovative solutions for others to follow. well versed in core data science competencies including statistical analysis and machine learning you will take a lead role in introducing the right technologies and tools for the job.\n\nworking as part of a talented team of application developers your responsibilities will include:\nproviding technical leadership in the area of data science.\nevaluating and implementing data science tools and technologies.\nresponding to requests for specific data insights.\ndiscovering and unearthing hidden stories as a catalyst for product development.\n\nyou will be able to demonstrate a clear track record of dealing with large volumes of dynamic data including examples of delivering insight to drive product and feature development.\n\ncv-library is one of the uk's largest online job sites, with over 10 million candidates and 3.8 million unique visitors every month. with a client list crammed full of the biggest brand names in recruitment and also a healthy mix of well-known corporate clients, we are rapidly evolving into one of the biggest and most dynamic online media organisations in the uk. the exciting news is we're still growing beyond all expectations including exansion into new markets around the world"

That job doesn’t seem too daunting. Memorise a few lines from the neural net wikipedia page for the interview and you’ll be a data scientist in no time.

Summary

Using the jobbR package and web scraping, we retrieved data scientist and data analyst job descriptions and visualised their different skill sets. Combining a bag-of-words model with a simple Naive Bayes classifier, we were able to predict (with approximately 90 % accuracy) the job type from the job description.

As always, I’ve posted the R code here. Thanks for reading! Please post your comments below!

Leave a Comment